Now we are 20

It started like this.

It is the late 90’s. Bill Mitchell, co-artistic director of Kneehigh, has been working in Cornwall on a series of outdoor, site-specific shows, together with artist David Kemp. Many will remember Ghost Nets at Godrevy and The Women Who Threw the Day Away at Botallack. Tiny budgets, high levels of passion, out in all weathers, exploring and experimenting with something that feels new and fresh. Then, there is a call from the Ministry of Culture in Malta asking if we would travel over to create a show in the City of Birgu. A Maltese arts officer has seen one of the Cornwall shows and is impressed. Bill, David and Mercedes Kemp travel to Malta to explore the place. We are met by a community on the brink of change, down at heel, neglected, besieged by problems but about to be transformed into a tourist destination. The location, overlooking the Grand Harbour, is staggeringly beautiful. The people are full of fear for what maybe coming their way. Developers are scouting the place. It reminds us of what Cornwall is going through.

We accept the invitation.

Bill, David, Mercedes, Sue Hill, Nix Rosewarne, musician Ian Wellens and maker Pete Hill travel to Birgu and start the process of finding local collaborators. A call for local artists results in an enthusiastic response. Paul and Liliana Portelli bring along their performer friends. Andrew Alamango joins us with his band, Etnika, and provides contacts with local brass bands. Meanwhile Mercedes is establishing contact with the local community. This involves total immersion in the life of the place. How do people live here? What do they value? What do they fear? What makes them proud? We are looking for a story that will reflect this community back to itself.

And here comes the curious thing: When asked about their memory of place the community consistently talks about the legacy of the Knights of St John, whose ancient buildings and forts are dotted around the city. A memory of the coloniser. So, a new plan is hatched. The community are invited to a meeting at the town hall and asked to bring their photograph albums. They arrive clutching shoe boxes, plastic bags full of images. And there it all is: Photographs of proud moments, showing off the first television set; women hanging long lines of laundry on the roof terraces; sad goodbyes to family emigrating far, far away; children, playing. Here are the memories we have been looking for. The show we create, Island of Dreams, emerges out of these memories. It reflects “not this city, but a city very much like this” back to the people who dwell in it and who are, themselves, part of the production and the story telling. Sets are built using what we find. A derelict boat, laundry tubs donated by the community, a JCB! A brass band marches us around the city and Etnika provides the underscore to our story. The Mayor and Councillors of Birgu play themselves. We even have the great, late Il-Budaj, a Maltese national treasure, join us to sing the show out.

At the end of the show, as we returned back to base surrounded by exhilarated crowds, Bill said:

“I don’t ever want to do anything else but this”.

And so, Wildworks was born.

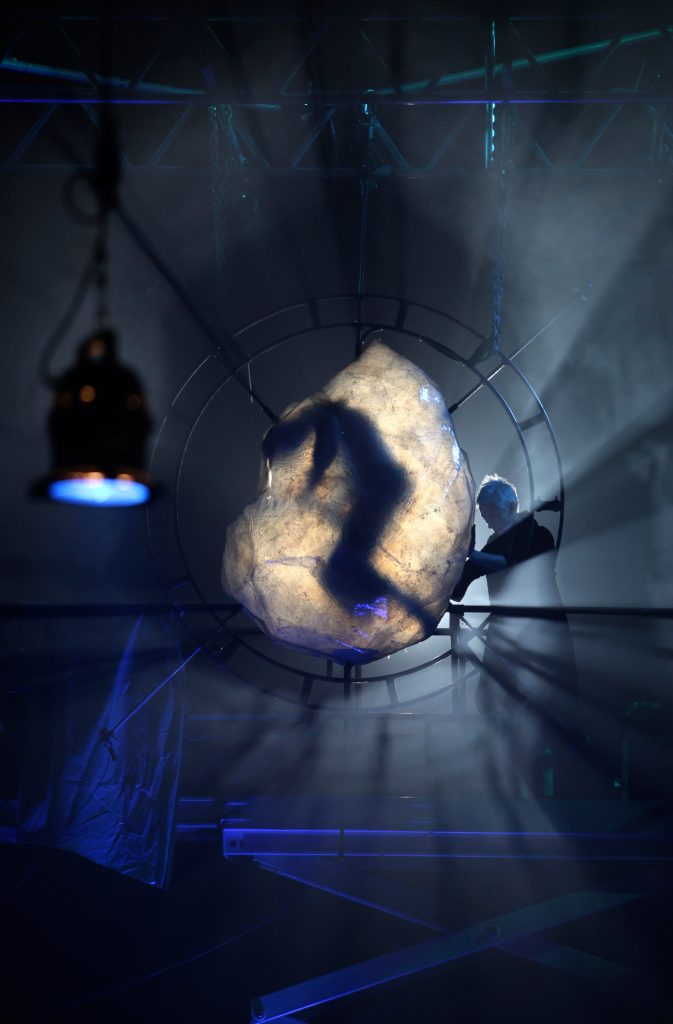

The founding artists, Bill Mitchell, Sue Hill, Mercedes Kemp, Nix Rosewarne and a very young Mydd Pharo who joined us for what would be our first production, A Very old Man with Enormous Wings which travelled to Malta and Cyprus under the Kneehigh banner and returned to Cornwall as fully fledged Wildworks, picking up artists and musicians along the way, creating new versions of the story on each site.

Our journey has always focused on learning and discovery.

These are some of the moments where we surprised ourselves.

They show the trajectory of the company.

You can find an extensive list of all productions on the Projects page.

A Story of Wildworks

Old Man with Enormous Wings

In Old Man with Enormous Wings, we discovered many things. That if you work outside conventional theatres, you get unconventional audiences. That we could draw people from different walks of life to help tell the story and become part of the experience. That we all start as strangers and nothing is taken for granted. And we did not take it for granted that ‘everyone will speak English’…The language of the show, spoken by a multicultural and multilingual cast, became the language of Mahal-le, and it bore traces of Latin, Malti, English, Spanish, Italian, Greek Cypriot, Japanese, gathered as we travelled.

An enduring memory: In Cyprus we worked in Nicosia, on the Green Line that separated the Turkish North from the Greek South. We worked with people from both sides of the border, who eyed each other suspiciously and didn’t even share a language. We asked one of the Turkish Cypriots to play us a tune from his village. As the music started the whole Cypriot cast, both Greek and Turkish, started to dance the same dance. Their shared history, prior to the invasion that separated them, was intact.

Souterrain

Souterrain travelled through the UK and France, finishing a two-year tour at Dolcoath Mine in Cornwall. In each different location Orpheus had to, once again, lose his beloved Eurydice and pass through the gates of Hades in his mythic attempt to bring her back. But each time the landscape he traversed was different, created out of the memory of people and place.

In Brighton we worked with a small community of residents living and working at the heart of Stanmer Park, a bucolic location. In Amiens we worked in a Napoleonic Citadel which had also been used as a Gestapo Prison during the occupation of the city in WW2 and as a reception centre for Algerians coming to France as a result of the Algerian War. In Colchester we worked in Keddy’s, an abandoned 1960’s department store. Our underworld here was of eternal shopping, escalators between the worlds, furniture displays where everything familiar is made strange, and angels of death circulate with special offers on heavenly scents.

In Hastings we work at a Comprehensive school. A school is everybody’s underworld, a personal pool of memory where we might gaze at our younger selves. In Gosnay we worked in a XVI century Women’s Chartreuse adjacent to a village populated by a community of miners struck by unemployment and the threat of marginalisation. At the geriatric hospital in Sotteville-en-Rouen we considered the fate of those who have crossed Lethe, the river of forgetfulness. The hospital sat in the middle of dense woods where lovers seek a final touch before bathing in the waters of oblivion. Our journey brought us, finally, back home to Cornwall, to the rich seam of memory that started it all.

In Souterrain we found we could emotionally engage the audience in and act of participation through a gentle invitation to leave their most precious memories in our safe keeping before crossing Lethe, the river of forgetting.

A memory: John Gapper, a resident of Stanmer Park in Brighton devoted to creating environments that would encourage the return of indigenous butterflies, had his elderly Land Rover turfed up and converted into a shrine to the returning butterflies. As the production progressed, he took it upon himself to stand on top of the turfed vehicle, watering it with a watering can each evening, as the audience processed through the street. He had created his own little Arcadia, a paradisical view of the afterlife.

Beautiful Journey

Beautiful Journey started with an obsession with shipyards and two texts: Constantine Kavafy’s poem Ithaka and Rebecca Solnit’s book Hope in the Dark. Ithaka alluded to Odysseus journey, suggesting that the essence of life lies in the experiences learned along the way, rather than reaching a destination. Solnit declared that “Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. It is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency”. In our show humanity is on the move after some catastrophic event. They arrive at Kalypso’s domain where they are enticed by pleasurable pursuits to stay with her and enjoy whatever time is left in her shanty town by the water.

The show took place at Devonport’s Naval Base and Wallsend’s derelict shipyards by the Tyne. We used cranes and forklifts, there was a massive block of real ice several tons in weight. Our performers looked out to sea from a cage suspended by a crane, hoping to spot reasons to be hopeful. The last iceberg arrived and was hauled out. Frozen within it, the body of a boy and a bee hive. And a young girl had the courage to take to the seas again, looking for a new start. Through Beautiful Journey we learned about the importance of using real artifacts and materials. When audiences saw the massive iceberg being carried in, they thought it must be a fake. But they could touch it. Feel the cold and damp surface. They became further immersed in the story and more invested in the outcome.

A memory: A small boat, made by hand for every show, sailed into the Tyne, which once carried the largest ships to the sea and was now completely empty, carrying a girl with a heart full of hope. Audience members who had known the river as a busy thoroughfare, weeping at the sight. Many of them had worked in the now quiet river.

Enchanted Palace

Enchanted Palace was a two-year installation in the State Apartments at Kensington Palace. We were doubtful when the commission was first proposed. A palace? Royalty? But initial research quickly revealed the sadness and humanity of those who had inhabited the place. The palace had been called “the aunt heap” as it became the residence of royal women who no longer served a purpose. We were intrigued. The original commission had asked us to create installations based on classic fairy tales. But the lives of these women were their own fairy tales, full of lost children, sudden deaths, broken families and many journeys into the dark, dark woods.

We told the stories of seven princesses: Mary, Anne, Caroline, Charlotte, Victoria, Margaret and Diana. All had to deal with their fair share of sorrow and loss, and we created rooms for them that carried the emotional weight they had had to bear, because they were barren, because they loved unsuitable men, because they were no longer wanted. We started the process by making a list of things you couldn’t do in a palace, and then we did them all. We filled the palace with sound, we played war games in the King’s gallery, we created a knitted throne, crown and globe and sceptre where audience members could play at being king or queen. And then we populated the palace with the Detectors, palace dwellers who roamed the palace seeking evidence of strong emotions and engaging audience members in their search.

Another question was, who is the community here? And they were there all along: the guides, the curators, the cleaners, the people who looked after the palace and loved it, and often had serious specialisms about the history of the place. They too became members of our team and became The Explainers, working in close collaboration with the Detectors to attend to the audiences and guide them through the spectacular installations created by our team of artists and designers.

Through Enchanted Palace we learned that no site is without human stories, communities and an emotional source to tap into.

A memory: A Spanish visitor was examining the battalions of toy soldiers in The Gallery of War and Play. He felt compelled to mend the wounds of war by standing up the fallen soldiers – giving them back their lives. He found the experience a great catharsis, as he let flow the history of his grandfather, who had been killed in the Spanish Civil War, leaving a family of refugees, displaced but strong with the love for each other.

The Passion of Port Talbot

The Passion of Port Talbot. The National Theatre of Wales commissioned Michael Sheen and Wildworks to create a show in the town of Port Talbot, in South Wales, where Michael had grown up. He was keen to create a secular Passion, as he remembered the community Passion plays that used to take place at Margam Park. For more than a year Wildworks worked in the streets, malls and social clubs of Port Talbot, finding stories, memories and images of the place. We found powerful locations where the story of the Passion would unfold. We walked the beach against the backdrop of the massive, smoke belching steelworks, sang songs in underpasses, searched for the ghosts of the people displaced from their homes by the building of the motorway.

We found many instances of the passions of Port Talbot people. More than 1000 people signed up to take part as performers, makers, writers, musicians, singers, stewards, messengers, angels and demons. The result was a huge spectacle that lasted from dawn on Good Friday until the evening of Easter Sunday, when the crucifixion took place in front of an audience of more than 20,000.

It was the most exhausting, exhilarating and satisfying thing we had ever done. And a town that had been neglected and ill-treated had their moment of pride, witnessed and celebrated by people all over the world.

Through The Passion we learned that, once a community is invested in a project, they will give their all, and that it is possible to manage a gigantic event through collaboration, co-creation and trust.

A memory: At the crucifixion site, on a roundabout at the sea front, after processing with Michael carrying the cross for many hours, followed by thousands and thousands of people.

The image of the crucified man, whose memory returns in the last moments, shouting names of old friends, the shop were people bought their trainers, the bus stop where young romantic encounters took place, and the audience shouting out in recognition, laughing and crying.

Babel

Babel. Olympic year in London. We were commissioned by World Stages London to create a show in collaboration with the Young Vic, Battersea Arts Centre, The Lyric Hammersmith and Theatre Royal Stratford East. The idea of Babel emerges as a strong metaphor for the world’s athletes gathering in London, a city were more than 300 languages are spoken. Every country and most languages are represented in the city. But, we asked, how many cultural groups speak to each other and in what circumstances? Where do cultures meet and why? We began to understand how rarely groups did mix, how many people and cultural groups are isolated. We decided our production would explore these questions.

We worked for two years in preparation. We worked with youth groups, beat boxers, choirs, LGBTQ asylum seekers, builders, mental health support groups, writers’ groups, knitters. We asked them to tell us their stories of belonging. We walked the city together. We built a 100 ft high tower out of bamboo at Battersea Park in one day, climbed it, and brought it down by evening. We built a city out of knitting and crochet. Our proposed location kept changing: From Battersea Power Station to Somerset House, to Elephant and Castle Council Estate. All fell through for different reasons. In the event our site was Caledonian Park, with its commanding clock tower which would become our centre stage.

We told a story about what it means to live in the city, about isolation and belonging, about home and homelessness. More than 600 participants and 9,000 audience were involved.

We learned that working across London is hard but, if participants feel loyal to a project, they will stay the course. Some of the participants had a three hour journey to reach the site, but they did not give up.

A memory: One of our participants, a Pakistani man, very quiet and self-contained, dancing Kathak on a small stage each night, magnificent, entranced. It turned out he was a master dancer in his country of origin, a national treasure. Until it was discovered he belonged to the LGBTQ community. His dance studio was burned to the ground and he had to seek Asylum in the UK. His dance was a dance of courage and hope.

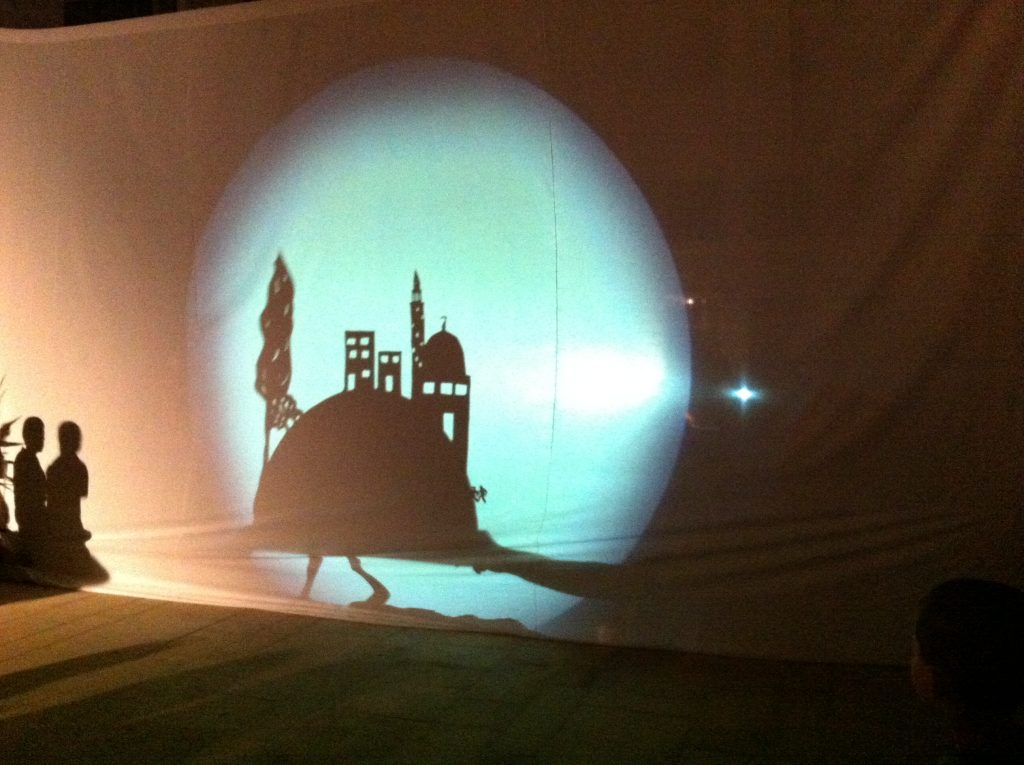

Nablus, City of Stories

Nablus, City of Stories. Bill, Sue and Mercedes travelled to the Occupied Territories of Palestine in 2010 to participate in the Palestinian Festival of Literature. What they saw and experienced had such a profound impact they were determined to return to create some work. At the time of visiting Palestine we were embarking on a series of very large site-specific projects where we would be testing the extent to which we could deliver our work to increasing numbers of participants and audiences with increasing technical resources. And we dreamed of going back to Palestine, to a more direct way of working, coming to unknown territory with few resources other than ourselves and our toolbox of methods.

With support from the British Council and in partnership with Project Hope, a local organization supporting education and cultural life, seven Wildworkers travelled to the West Bank. Project Hope became the backbone of local support. They made their offices available to us, facilitated many, many encounters, provided us with translators and interpreters, found locations and generally threw open the gates of Nablus to Wildworks. We followed a number of invitations to talk to people in their homes, visit particular neighborhoods or walk to the sites where particular stories had taken place. This was an intense process of witnessing and experiencing extremes of emotions. We worked in the city and the adjacent refugee camps. We heard stories of displacement, loss, death, hope and resilience. We were far away from home, away from our usual materials, tools, props and technical back up. We picked visual media that lent itself to the situation to provide maximum effect with minimal resources: film and projection, Shadow theatre.

We found a thriving music scene through the Edward Said National Conservatory and the Dabke groups. Our musical director worked with them to create a soundscape for the stories, as they emerged.

On the last evening of the Wildworks residency we shared the work with an audience of several hundred friends, family, supporters, funders and other guests.

The evening wove each story together: text, performance, music, projection, shadow theatre and light came together in an expression of the city and its people.

We had packed our bags; we were leaving in the morning. We were having one last cup of mint tea in the courtyard of our guesthouse, Beit-el-Sham, when we received a surprise visit from the young men of New Askar Camp, come to send us off in style. It was a very moving moment, and a fitting end to a residency where Wildworks had been received with total generosity, trust and hospitality.

We learned that we could go back to our roots, work with minimal resources, rely on the power of story to create meaningful works. That what really matters is the connection with people and place.

A memory: Mercedes met a young man, Mohammed, a footballer. He had just been picked for a trial with Roma Football Club. He was reluctant to go and leave the grave of his friend Odai. This is the story he told.

He performed by himself against a projection of Odai’s image. It was the very first time he had performed in public.

Odai, I remember when we were children. We were friends since we knew life.

We lived very near to each other. Both in the same street.

We played football in the street every day, we were good.

One day, when we were playing on our street, we heard the army coming.

And we ran through the streets.

All the children in the camp ran towards the olive field in the mountain.

We ran through the streets and we could hear the tanks coming.

They were always coming…

We could hear the gunfire. We reached the olive field.

We could see the army coming, shooting tear gas and real bullets at us.

We were throwing stones at the army.

We shouted: “This is our land! You can’t come here!”

We were only children.

The army were coming, shooting at us.

We all ran back, all of us, but not Odai. He was alone, facing the army.

We were hiding behind the cactus. We shouted: Come back Odai! Come and hide! But they didn’t.

And then Odai was shot.

We wanted to help him, but the army were still shooting.

We couldn’t reach him.

When the army retreated, we ran towards Odai.

We asked some people to call an ambulance, but the ambulance didn’t come.

I went to Odai. When I reached him, he breathed his last breath.

We carried his body through the field.

I went to his house. I told his family he had been shot.

Afterwards, I was broken.

My life had changed.

I had to learn to do everything without you, Odai.

My friends helped me.

My family helped me.

But most of all, playing football helped me.

I came to this field to play every day.

And every week, I came to visit your grave, my friend, Odai.

I became very good at football. I joined the Palestinian team.

And then I got this opportunity to go to Italy and play for the Roma team.

I want to do this for two reasons, Odai.

One, for myself, and for my talent.

The other one, for you, Odai

Odai, I am leaving, I am very happy to have this chance.

But I am very sad also, to leave my family, my friends, and you, my friend.

The ghost of Oday speaks

Mohammed! My friend!

Go and triumph for the both of us!

For a better future!

(Text transcribed as it was told and recrafted in conversation with the teller.)

Once and Twice Upon a Castle

Once and Twice Upon a Castle. Kasteel van Gaasbeek is a castle located in Lennik, Flemish Brabant, Belgium. It was erected around 1240 and is surrounded by a huge park. We were commissioned to create a two year installation. The castle’s history is right at the centre of the creation of Europe as a political entity. We started with the premise ‘What if the stones could talk?’ For a whole year we researched the site, both through conversations and workshops with the people who look after the castle and through an exploration of its extensive archives, dating back over several centuries.

In the end we were captured by three characters: Lamoral, Count of Egmont, the hero; Paul Arconati Visconti, the visionary and Marie Peyrat, Marquesina Arconati Visconti, the collector and cultural patron. There were traces of their lives everywhere: boxes and boxes of correspondence, diaries and journals, maps, photographs (or, in the case of Egmont, contemporary cartoons of his execution). There were key discoveries that provided the foundations for “Once upon a Castle”. Finding the text of Egmont’s passionate last letter to his wife Sabine, and the cold, cynical correspondence between Philip II and the Duke of Alba after taking Egmont to the scaffold. Paul Arconati Visconti’s astounding notebook “Culture et Recettes” where he reveals himself as a practical visionary, his correspondence with world leaders proposing a plan for world peace and the densely hand-written journals where, at the end of his life, he begs a Higher Being for the salvation of his soul. Marie Peyrat’s extensive correspondence, lively and opinionated in her prime, and reflecting the sadness of her decline after the death of the love of her life.

We created a series of spectacular installations based on these stories. And the castle stones spoke through sound installations. Five hundred years of letters and diaries were heard as visitors progressed through the rooms. There are many ways of understanding history and many paths to the interpretation of the traces left by human lives. Our way is to search for human emotion. Our treatment of history seeks a poetic vision that is grounded in documentation, but undergoes a series of transformations through visual art forms, performance, poetry, music, sound.

Through Once and Twice Upon a Castle we gained confidence on our ability to bring history to life in unexpected, highly visual ways. And that the people who tend to the place, guides, cleaners, gardeners, curators, are the best suited to populate our installations, bringing them to life.

A memory: In the Room of Europe, we created a magnificent dinner party presided over by a huge Cake of Europe. The dinner party became a metaphor for a kind of political game… a big boys party. Visitors sitting at the table. Who will get the biggest slice of the European cake? Are there deals to be done? Are there quiet conversations to be had in the corner of the room at an appropriate moment? Lobbying to be done? Bribery?

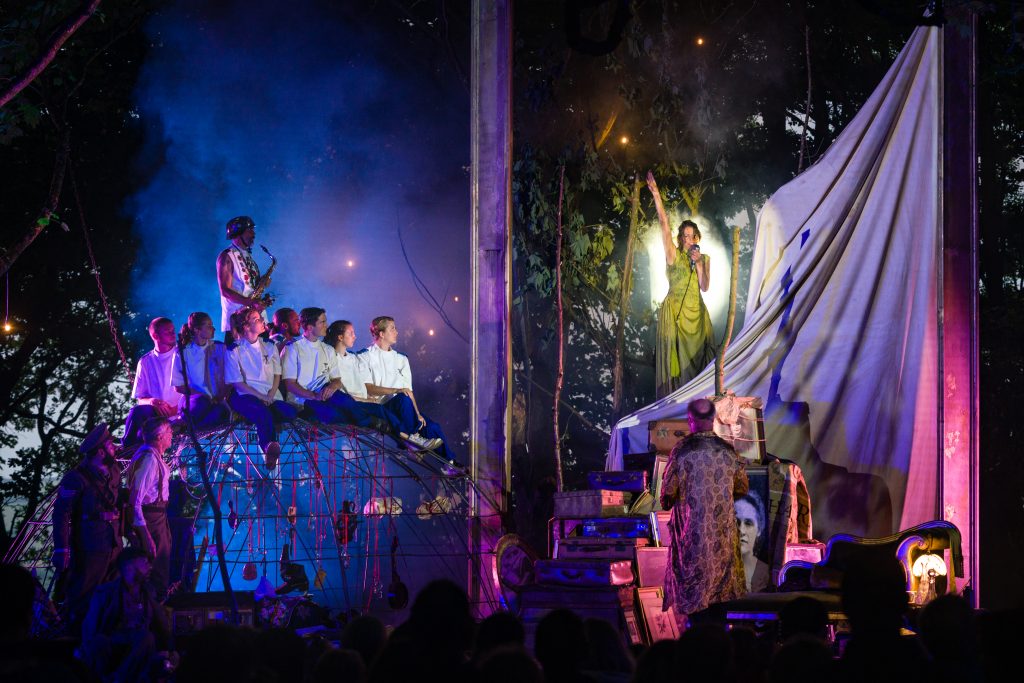

Wolf’s Child

Wolf’s Child grew out of an exploration into the wild and the civilized, the animal in humans and the human in animals. We spent a week in Tehidy Woods in Cornwall exploring these themes with Dr Chris Seeley, bear expert, and Sean Ellis, who lived for two years with wolves, becoming a member of a pack. We explored myths of metamorphosis, the myth of Callisto, who was turned into a bear by jealous Hera, and whose father had been turned into a wolf by Zeus. We became wolves and crows, roaming through the woods, howling.

The show opened at Felbrigg Hall, Norfolk, as part of the Norfolk and Norwich Festival and then came to Trelowarren, Cornwall. It was important that both locations had a stately house at the centre, surrounded by wild, tangled woods. The houses became the home of a chorus of young women straitjacketed in stiff white collars and in the care of Mother, a strict guardian hellbent on knocking the wild out of the girls. But it wasn’t long until one of them, Rowan, ran with the wolves. Into the wild and in lupine company she soon became pregnant and gave birth to a child, Thorn. Was it a human child? A wolf? Or something in between? Audiences traversed the woods guided by mournful crows. Rowan had to die but Thorn, our wolf’s child, chose the path of the wild, walking into the forest without looking back.

Through Wolf’s Child we learned that we could carry sound with us through the most tortuous of landscapes. Performers had mini rigs attached to their costumes so there was no interruption to dialogue, songs and underscores. The howling needed no amplification.

A memory: At the beginning of the show the entrance of Mother riding a magnificent shire horse and carrying the body of a bleeding wolf across the saddle, surrounded by fiercely corseted maids. As the sun sets the howl of the wolves can be heard in the distance, a prelude to all that is to come.

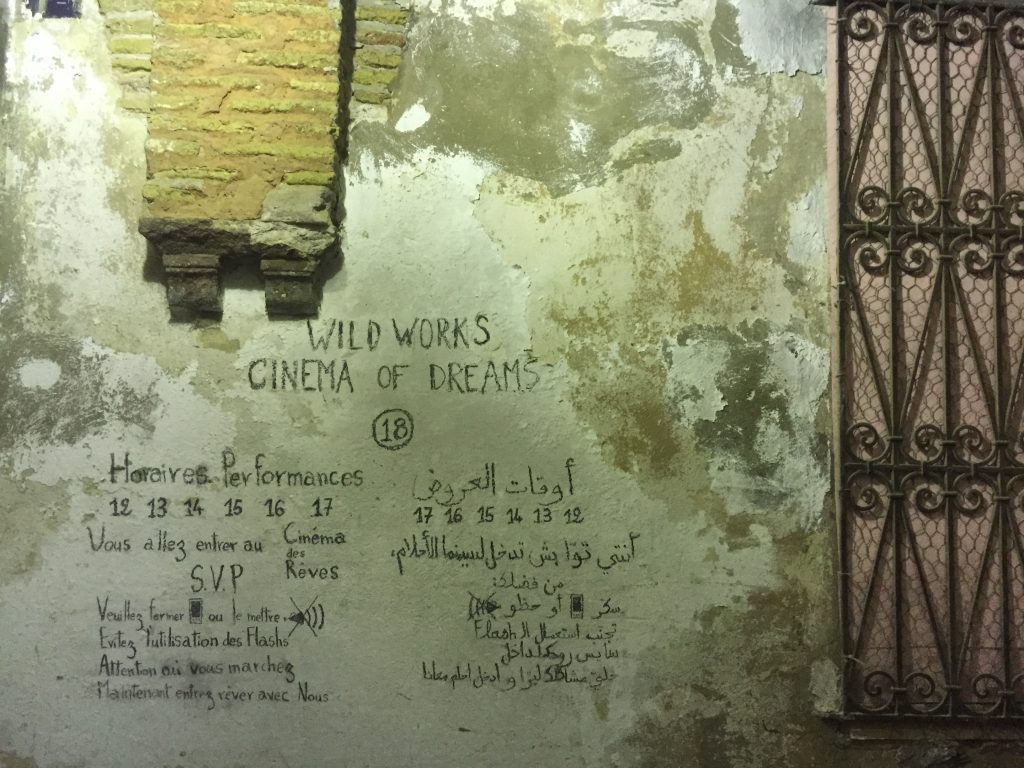

Cinema of Dreams

Cinema of Dreams The Arab Spring. In Tunisia the Jasmine Revolution has deposed Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and visionary local artists Sofiane and Selma Ouissi have set up Dream City, the Tunisian Biennale for Contemporary Public Art. And we are invited to participate. Their mission is to recover the streets for the citizenry. Supported by the British Council three Wildworkers travel to Tunis in the spring to carry out research. The city is alive with excitement, though there are still tanks on the streets. The attack on the Bardo Museum, leaving 22 dead, has just happened. We walk through the Medina, the old city, through condemned palaces, secret gardens, sealed warehouses. The image of one particular building stays with us. A tall wall with bricked-in doors and windows. In the centre, a curious feature signposts the building’s former use: Twin ticket booths crowned by graceful arches remain. This was once a cinema. The image brings associations of the cinema as a communal space of dreams. Here is the thread of an idea. We start talking about memories of going to the cinema with people we meet. We do this casually, just testing the initial response. Curious. The responses are immediate, detailed and enthusiastic. The idea starts to grow. We met Hashem Ben Ammar, a distinguished film maker, who introduced us to 100 years of Tunisian film making, from Chikli to the bloggers of the revolution. We propose to create a surreal dream cinema at the Majden of the Rue de Dey., an old Ottoman warehouse. This will be our Cinema of Dreams. We commission Hashem Ben Ammar to create two short films, written, directed and performed by the children of the Medina.

We return to Tunis in the autumn, just after the attack on the beach at Soussa which left 38 dead. In spite of the precarious safety situation the city is alive with excitement. Artists from all over the world are here to create work alongside Tunisian artists. The children’s films are ready. The premier of the films, in a large cinema in the centre of Tunis, was an emotional and beautiful affair. The cinema was packed with the children, their families and all the artists involved in the making of the films. For the children, there was an intense sense of validation.

We find a team of volunteers who will assist us in creating our installation and will also populate it as performers. Through film and installation, we create a space where memory and hope coexist. Audiences travelled through a space filled with memory to arrive to a room where the children’s films, the hope for the future, were projected

Old and young citizens of the Medina contributed to this project. The elders reminding us of where we come from so we may not forget. The children, gazing into an imagined future, showing us that, to make anything happen, we have to dream of it first.

Through Cinema of Dreams we learned that art has a role in mobilising communities who have experienced trauma. That the thirst for self-expression is as strong as that for more immediate physical needs. Working on Dream City had a re-invigorating effect. It reinforced our values and created bonds with the people we worked with that will endure into the future.

A Memory: The spirit of generosity and hospitality, and the sense of ownership for the space we created together with our Tunisian collaborators. It was a delight to see the performers dealing with a range of audiences with such care. The day we had 45 children, how well behaved they were and how the performers devised ways of making their experience great. How attentive performers were to the audience mood, and to anyone who might need special care. It was very moving.

100: The Day Our World Changed

100: The Day Our World Changed It’s the centenary of the outbreak of WW1. We are commissioned by 14-18Now to create a piece at the Lost Gardens of Heligan, who will be our partner in this production. When The Lost Gardens of Heligan were discovered back in 1990, the most significant excavation exposed a faded list of names scrawled on a crumbling wall of the old gardeners’ toilets. One of these was soon discovered to be that of a young man who enlisted and lost his life in World War 1. Subsequent research established that Heligan had lost many of its outdoor workforce. And most of their names were recorded on the war memorials of the three local villages; Mevagissey, Gorran and St Ewe.

For a year we worked in the three parishes. We held a number of tea parties calling for people to bring their photographs, memories, anecdotes and the traces of the family members and friends who had been caught up in the events of 1914. At the same time, we carried out archival research, carefully recording the names of all the lost men of the parishes, checking their military records, the cemeteries where they rest, the places where they crossed paths with history. We held a number of workshops for community performers and singers. These were the people who would populate the world of 100: local dignitaries, gardeners, soldiers, fishermen, families. We worked with the gardeners and estate workers at Heligan, who would perform as their forebears from 1914. Heligan staff were also instrumental in growing the sets for 100: The field of corn and poppies, the field of home and war. The battlefields and graveyards of the Somme.

The result was a dawn to dusk event. The day started at dawn, with the calling of the names at each Parish Memorial. We then moved to Mevagissey, and watched a lugger coming to port carrying the Naval Reservists, who would be the first to leave for war. We followed the men walking out of town. The rest of the day took place at The Lost Gardens of Heligan. Audiences could wander around the site at will. There were scenes of intimacy set in contrast to wide, panoramic views of epic moments: Women and children gathering the harvest whilst soldiers charged into a raging battle, mass graves, the burning trees of Passchendaele. The simplicity of the film-like long shots was moving because it was a fusion of place, people and history. 6,000 audience attended 100: The Day Our World Changed.

Through 100 we explored how cinematic conventions might translate to a live event, playing with the intimate and the panoramic and experimenting with slipping time, creating an immersive experience for audiences and participants.

A memory: The finale, when the names of 53 men lost from the 3 parishes were read again, each accompanied by a short, personal memory, held the audience in respectful, entranced silence as they watched the ghosts of the fallen walk into the distance, towards the sea. We were able to gather fragments of information from family memories, archival documents and our own surmising, based on the information we gathered. A hugely emotional moment.

Walter CLOKE, 22

He knew his way on the water and how to sail close to the wind

Killed at the Battle of Jutland

Thomas Henry DONNITHORNE, 20

He was a carefree young boy, looking for adventure. Adored by his mother and sisters. The women of his family visit his grave to this day.

Killed in the 1918 German Spring Offensive

William DUNN, 25

He was born by the water and could handline from the harbour wall before the age of five

Killed in the 1918 German Spring Offensive to the West of the town of Perronne.

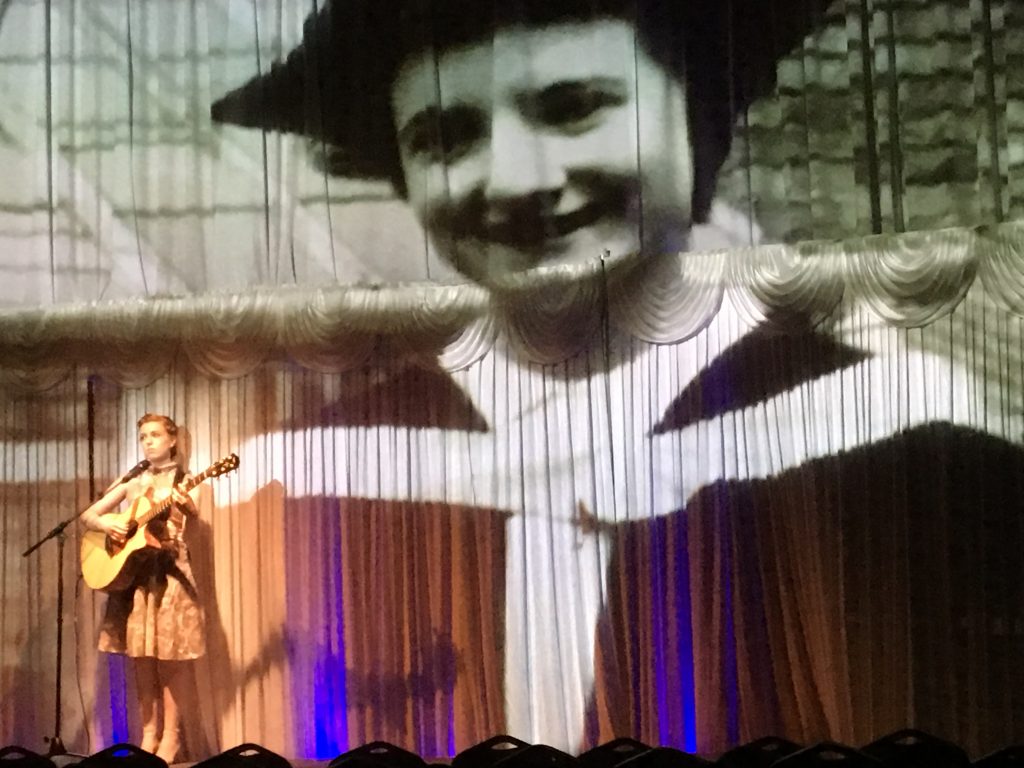

A Great Night out

A Great Night out

We were commissioned by Cultural Spring, a Creative People and Places project, to create a piece of work with the communities of Tyneside. We started with the idea of an event loosely modelled on The Canterbury Tales, where different characters would come into the space and tell their stories. For over a year we visited Sunderland finding individual stories that were also representative of communal feelings, values and hopes. We also audited local talent that would contribute to A Great Night Out, an evening of glamour, enchantment, music, food and powerful tales. In sitting rooms, cafes and working men’s clubs in Southwick, Hetton, Castle Town, Sunderland, St Peters, Easington, South Shields, we listened to stories of pride, comradeship, love, fun and passion. We found the music that is the heartbeat of the place, creating collaborations with musicians young and old, swapping tales and rhythms. From the Ukelele orchestra to Ross Millard from the Futureheads, who became a close collaborator of the project, around sixty musicians, both professional and amateur, created the soundtrack to our show.

We told the tale of the young woman who everyone said was destined for marriage but who went to university and became a powerful force for her community. The young man who was forced into mining but, trapped in a mine collapse, kept dreaming of sailing the frozen North. The miner and the policeman who were forced into opposing sides during the Miners Strikes. The women who supported the strikers with everything they had. The footballers who were the pride of their community. The shipworkers who sent massive ocean liners into the sea. The music teacher who played songs to the dying with his homemade guitar in the Japanese prisoner camps in Burma. The evening took place at The Point, a night club turned for the event into a Working Men’s Club, a glittering dream space, and was hosted by the wonderful Ray Spencer, who appeared yearly on the South Shields Panto. Local helpers served bubbly and canapes and A Great Night Out was had by all.

Through A Great Night Out we re-affirmed our belief that even the most down at heel communities are a hot bed of talent and that they have many heroic tales to tell. We are nothing without them. A Great Night Out was their night.

A memory: The great, late Len Gibson, aged 98 at the time, had been talking to us for a year about his life. He was a music teacher who found himself in a prisoner camp in Burma, had made a guitar out of stolen bits from the Japanese, and sung songs to the dying in the cholera huts. Meanwhile his wife, Ruby, who was the nurse who cared for him when he returned, was fading away in the bedroom. She died just before the show. He was moved to perform the song they loved as a young married couple, accompanied by his guitar. On the night, against a huge projection of Ruby’s face, the room flooded in red light, he sang like an elderly angel. We have never seen an audience so moved. Tears and three stand up ovations saluted this tender heart who touched us all. Spending time with him was a gift.

AND THEN BILL LEFT US. He was working, and talking about work until the very end. Overwhelmed by grief we continued preparations for the project we had been working on…

100: UnEarth was

100: UnEarth was the companion piece to 100: The Day Our World Changed, also staged at the Lost Gardens of Heligan. Thirteen men left Heligan to join the forces in 1914. Of the thirteen, only four returned. 100: Unearth commemorated the end of WW1 but we also wanted to explore the links to contemporary conflict. We worked with a number of veterans from recent conflict and their families, gathering material that would inform 100: UnEarth. We conducted a number of lengthy interviews where the veterans and their families were invited to share their experiences, many of them for the first time. We were honoured to gain the trust of the veterans, most of whom suffer from PTSD. They were all guests of honour at 100: UnEarth performances.

For 100: Unearth we reworked the story of Orpheus and Eurydice which we had told in Souterrain. Orpheus returns to his beloved wife Eurydice. On the day they are reunited she is killed in a tragic accident. Orpheus cannot accept her death and embarks on an audacious quest to pluck her out of the Underworld. A journey between the worlds…In 100: UnEarth there was a clear distinction between the world of the living and the world of the dead. A world within a world. The world of the living was firmly set in the context of the first World War. The war has ended. The men are coming home. Many are damaged, broken. They return to the families they left behind. Their women have learned to survive alone, to be self-reliant, work the land, feed themselves and their children. Nothing will ever be the same… At the centre of this is the encounter between Orpheus and his beloved wife Eurydice. There is such hope in this moment, as if all the suffering can be put behind, as if there can be a new beginning…But death is not far, it hovers over the men like a shadow. In a random accident with a hand grenade Eurydice is killed. There is a moment of total silence, but for the sound of birds flying out of trees, scared by the outrage. And then sergeant Hermes, Orpheus companion, intones his Farsi Lament, sings it out into the landscape, carrying with it all of the sorrow of a lost land and a lost people. And this is real, because Mohsen Ghaffari, who plays Hermes, has brought this expression of grief from his native Iran, reminding us that the war we are remembering was not, after all, the war to end all wars.

The world of the dead is an altogether stranger place.

We arrive from the world of 1918 to a place where all times co-exist This strange border post is staffed by angels of death. There is a Tannoy system that gives direction. We soon realise that this is one of many gates into the world below. We hear instructions:

Staff announcement, staff announcement. Border operators to gate 35 D. A consignment of souls from Fallujah awaits processing. Numbers confirmed at 1,251.

Staff announcement, staff announcement. Border operators to gate 12 A. A steady arrival of souls from Gaza, numbers unconfirmed

We become aware that all the dead from all wars are arriving at this place. And the numbers are genuine. But there is another point we want to make. The numbers of the dead entering the underworld in more recent conflicts are all civilians. Because this is what war has become. Total war, where civilian populations are the first victim.

Our conversations with veterans resulted in the images that populated “The Garden of Lost Souls”, an area of the Underworld where souls endlessly played and replayed moments that had had an impact on them and from which they couldn’t move on. A veteran told us about sailing home at the end of the Falklands conflict. The ship was transporting exhausted troops back home. It was a long journey. There was a cinema on board and the men were encouraged to select their viewing each evening. There was a wide choice of films: Action films, Westerns, X-rated movies. Every night without fail the men chose to watch Walt Disney’s Peter Pan….And here they are, in the garden, endlessly watching the Lost Boys… In our Underworld we followed the logic of the garden, where death and regeneration follow each other in and endless cycle. Where every wound and every burn is a flower bursting upon the suffering bodies of the victims.

100: Unearth was staged by a team of over 40 professionals and more than 200 volunteers. Its reach was extended by three projects that travelled the communities of Cornwall and beyond, through digital means: The Knitted Torpedo, The Field of Loss and the Wall of Love, all of which invited contributions to the show.

100: Unearth was suffused with our grief over the loss of Bill. But we learned that we could carry on, that our work would continue.

A memory: Over the tall wall that separates the Melon Yard from the Productive Gardens, a row of gardeners stood, wearing helmets and brandishing their shovels like weapons, as if ready to go over the top. One by one they descended and brought shovelfuls of earth which they deposited on one of the pineapple beds for which Heligan is renowned. As they returned back to their positions you could see that the backs of the shovels were inscribed with the names of the battles in which they died. So, our metaphor of gardens and regeneration was, perhaps, at its more powerful here, as if the gardeners were bringing soil from the battlefield to create a new garden, from grave to flower bed, defying loss and oblivion by a simple act of tending the earth.

The most moving thing is that our gardeners were played by the workers who tend the Heligan grounds today and who, every day for three weeks, after a long day’s work, donned their costumes to pay homage to those who had come before them. Both men and women took on these roles. We even had a young man whose great grandfather had been one of the lost gardeners. They took it in shifts every night, sometimes six of them, sometimes eight or nine, depending on availability. On the last night of the show a team of thirteen climbed on the wall and looked over the horizon, a full complement bringing back to life, for a brief moment, the thirteen that went away in 1914.

… We mourned for a year and then Mydd became our Artistic Director, a fitting successor to Bill. And then the Pandemic struck…

Meet Me at the Edge

Meet Me at the Edge In the thick of the pandemic we wanted to create work that resonated with the moment we were living.

There are times when one hangs

Suspended, hovering

Between the past and the future.

There aren’t very many times like this

Lightheaded, pregnant with possibility,

Wondering where

The next footstep

Will fall.

This is one such.

(Mercedes Kemp)

Our Artistic Director, Mydd Pharo, Musical Director, Vicky Abbott and writer Mercedes Kemp were all living in the farthest reaches of West Penwith, at the edge of the land. The site of Botallack Cliffs, our back yard, was the ideal site to create work where we could keep audiences socially distanced and explore what it meant to be on the edge, both literally and metaphorically. The edge of the world, the edge of solitude and loneliness, the edge of love, the edge of tolerance and endurance, the edge of meaning and the edge of the land and the sea.

We wanted to explore the possibilities of binaural sound, which creates a 3D soundscape, especially when listened to with headphones. We created a soundscape which combined Mercedes experiences of living on the edge of the land for fifty years, Vicky’s amazing choral compositions and the experiences of community members who had encountered different “edges”. We would then populate the landscape with the people who had given us their experiences and have the audience sit on the cliff edge, absorbing the majestic meeting of land and ocean and listening to the soundscape through headphones. The preparation of the soundscape was complex: We had to record everyone in socially distanced settings and the choir was recorded in groups of two and three at the Miners Chapel in St Just, then mixed in the recording studio. We were ready to go. The show was to roll through a day, starting at dawn and repeating every two hours until sunset. And then, on the eve of our performance, the second lockdown was announced and we had to cancel. We were able to do one run with friends and family. It was disappointing, but we were not deterred. Meet Me at the Edge became a film. All the elements we planned were included, with the added bonus that we could film our community participants in their own settings. It was a very moving piece that we were proud to have achieved under very difficult circumstances. You can watch the film here.

Through Meet Me at The Edge we learned that we could adapt the medium to the situation we found ourselves in. We also made a version of the film that was entirely in British Sound Language, which we had started to do on 100: Unearth and has become a feature of all subsequent work.

A memory: Working at Botallack cliffs day after day with the choughs doing aerobatic displays and pods of dolphins leaping far below.

I Am Kevin

I Am Kevin started with the myth of Myrrah and Adonis. Pregnant Myrrah was transformed into a tree to save her from her pursuers and gave birth to Adonis. Born out of his mother/tree, young Kevin grows up within a protective perimeter created by his mother and lulled to sleep every night by stories of the monsters that live outside the circle. He must never leave or he’ll face his own destruction. A prophecy of doom hangs over his head and he must be protected. When his mother disappears, he is lured out of the circle by a Stranger and together they embark on a journey through a world of gods and monsters. But nothing is really the way it seems. Are the monsters really so monstrous? Is the Minotaur a people eating beast or a broken boy neglected and imprisoned by his father? Is Pandora a foolish girl or a woman haunted by the horrors contained in the box she dared to open? Are Daedalus and Icarus the victims of their own pride or are they trying to escape unjust imprisonment? And where is mother? Through his journey Kevin comes of age and learns to let go of the past and imagine a new future. I Am Kevin was a tale of fate and loss, of facing your fears and learning we have the power to re-write our own stories.

I Am Kevin was set at Carlyon Bay beach, in the St Austell area, against the ruins of the old Coliseum, a concert hall that once brought music from all over the world to this Cornish site. We ran community workshops for several months and created quilted story fabrics that would become the skirts of Kevin’s mother and the chorus of Fates. We recruited participant volunteers and a community choir. We promenaded our audiences along the beach on the balmy nights of a scorching summer. Performances were filmed several times and turned into a feature film which toured Cornish Cinemas and was featured at the Celtic Media Festival.

Through I Am Kevin we learned many things. We perfected the art of taking sound with us across the beach, the performers carrying speakers so that music would be uninterrupted throughout the performance. And we affirmed our belief that our work can be successfully adapted to the medium of film. That our performances are cinematic and our films theatrical.

A memory: On a full moon night a funeral procession, carrying tree branches aloft, walks towards the audience from a great distance, singing a haunting song of mourning. An intensely emotional and moving moment.

We Are Shining

We Are Shining

We received a sizeable grant from the Cornwall and Isles of Scilly Good Growth Fund (UK Shared Prosperity Fund). The title for the project, We Are Shining, came from research into Pytheas of Massalia, a Greek navigator, geographer and astronomer who, around 325 BCE circumnavigated the British Isles, arriving in Cornwall and naming it Belerion, the shining land. His writings were not preserved, but The Greek writer Diodorus Seculus quoted him during the first century BCE as saying They that inhabit the British promontory of Belerium (Cornwall), by reason of their converse with merchants, are more civilised and courteous to strangers than the rest are. ‘These are the people that make the tin, which with a great deal of care and labour they dig out of the ground; and that being Rocky, the metal is mixed with some veins of earth, out of which they melt the metal, and then refine it: Then they beat it into four-square pieces like to a dye and carry it to a British isle near at hand, called Ictis.’ Ictis is thought to refer to St Michael’s Mount. So, we imagined what it would be like for a stranger to arrive on our shores. What would we like to show? How would we like this person to be welcomed?

We Are Shining was made up of a number of projects. We wanted to share with as many local artists and communities as possible. We started with Re-Wild, a series of residential workshops for artists, teachers and partners, which sought to introduce our ways of working and methodologies to those who would be working with us. The workshops took place in the beautiful Trelowarren Estate. For a month we played, created and shared with participants.

Out of these workshops a number of artists proposals were submitted. These formed Hello Stranger, ten artist led community projects and 4 school projects spanning the area from the Tamar to the Isles of Scilly, working with the homeless, the disabled, refugees, the Woman’s Institute, choirs, the bereaved and many more. The premise was to present snapshots of Cornwall today to the imaginary stranger arriving on our shores and re-imagining what this ‘Shining Land’ means to us today.

In July we created The Kneebone Cadillac, staged at United Downs Raceway near St Day in the heart of Cornwall’s mining country. A feisty, riotous show, a highlight of the We Are Shining project and loved by audiences.

The project culminated with Stranger Beasts. On the cliffs of Geevor tin mine, in the farthest reaches of the land, an iconic site and spiritual home to many Wildworks artists, we set this story, where Belerion, Cornwall, was embodied in the character of Bel, a wild girl born of a planetary mother and an earth-bound father whose cruel destiny was to grow up motherless and exploited, quarried, gouged and excavated by those who wished to tame her. Until the day a Stranger arrived in a storm, summoned by Bel’s rage, and held a mirror to her wild beauty, reminding her of her true nature and her capacity to transform herself, over and over again, through the power of love.

Stranger Beasts took audiences on a wild walk through the extreme landscape of Geevor, the weather throwing wind, rain, fog and everything this stretch of coast can deliver in any season, but also some balmy evenings and astounding landscapes. The story reminded us that nature will necessarily triumph, even in the most toxic of landscapes, endlessly regenerating itself, tenaciously clinging to the granite as Bel grew up ‘wild as gorse, tough as heather, with the fierce intensity of the kestrel.’

A tragic tale, but also a tale of hope.

Stranger Beasts was a challenging project in terms of the hard terrain, the technical demands, the extreme weather, but one so very close to our hearts. It reminded us that our passion will overcome all obstacles and that our audiences will stay with us in severe conditions because they are themselves part of the story and everything that is at stake. And that even the harshest of weathers is our friend, adding drama and atmosphere to the site and the work.

A memory: Our Stranger, arriving from the sea in dense fog, carrying a flare and traversing the landscape like a fiery ghost, running towards Bel.

These are not all the shows we have made. There are many more which helped us explore ideas and find our way towards larger-scale work. You can find them all on our Projects page.

The Founding Artists

Bill Mitchell

Visionary artist and director, Bill originally trained as a theatre designer at Wimbledon School of Art. His early work was with community theatre company Perspectives in Peterborough, a socialist collective, where he

started to find his voice as a theatre maker. It was here that he met Sue Hill (Wildworks Founding Artist). He was a brilliant visual storyteller, his craft honed in making compelling work for children and young people with Theatre Centre, the Young Vic, Avon Touring, Theatre Foundry and Nottingham Playhouse. He and Sue moved to Cornwall in 1988, joining Kneehigh and helping to grow their vibrant physical performance style. Bill designed and directed many Kneehigh shows taking their work outdoors and developing immersive theatre journeys, Wild Walks. In 2005 Bill set up Wildworks to develop Landscape Theatre, making work both epic and intimate, grown and harvested from place and people.

Lyn Gardner captures Bill’s genius in her obituary for The Guardian…

‘Mitchell and his team created a string of memorable shows including A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings (…based on a story by Gabriel Garcia Marquez), a haunted version of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth called Souterrain and the spine-tingling The Passion, a contemporary, secular version of the Easter story. A 72-hour event unfolding in real time over Easter weekend in 2011, and starring the local hero Michael Sheen, The Passion was made with and for the people of Port Talbot. The Last Supper took place in the local social club with interventions from the Manic Street Preachers, the Garden of Gethsemane was an earth-filled skip on a housing estate, while angels pedalled on fiery bicycles and the sea become a massive baptismal font. It was, and is likely to remain, one of the great theatre events of this century’

Sue Hill

Theatre-maker, artist, gardener, writer, maker of figurative sculpture out of mud, sticks, steel and plants, Cornishwoman.

Founding Artist of Wildworks. Sue was Bill Mitchell’s partner in life and art from 1978 until his death in 2017. She has worked as a performer, designer, maker, writer or director on many Wildworks projects. She led and curated the Bill’s Attic project, a creative playground for artists using Bill’s extraordinary collection of artefacts and imagery. With Kneehigh she was instrumental in originating several festivals that have now become part of Cornwall’s calendar – Golowan in Penzance, City of Lights in Truro and the lantern procession on Tom Bawcock’s Eve in Mousehole.

Sue has travelled widely, making theatre in unlikely places with Kneehigh, Wildworks and Scary Little Girls. With her brother, Pete Hill, she has created many iconic large scale earth sculptures including the Mudmaid and Giant at Heligan, Thousand Mile Eye in Hong Kong, Ardhi in Kenya and Eve at Eden. She was Artistic Director of the Eden Project for seven years, she now works on new Eden Projects in development for Qingdao, Dundee and Morecambe. She is an Honorary Fellow of Falmouth University and a Bard of Gorsedh Kernow, bardic name Gwriores a Gewri ‘Maker of Giants’.

Mercedes Kemp

Mercedes Kemp was born and grew up in Andalucia. For the past fifty years she has lived in West Cornwall. After working in collaboration with Kneehigh for some years she became a founding artist of Wildworks, developing storylines and text for site specific pieces all over Europe, the Middle East and the UK until today.

As well as the production of text and story line, her role within Wildworks involves creating and maintaining relationships with host communities and exploring their relationships with place and memory.

Her method involves a kind of eclectic ethnographic research into a variety of sources: archives, libraries, cemeteries, village halls, bus stops, local historians, town gossips, snapshots, old photographs, conversations, and, above all, a close observation of the process of memory and its effect on the value that people place on their environments.

Mercedes brought to the company a Mediterranean sensibility and a magical realist sense of the world as well as a passionate love for Cornwall, her adopted home.

Mercedes was Senior Lecturer in Fine Art and Creative Writing at Falmouth University for thirty years until her retirement in 2021. She continues her journey as a Wildworker.

Nix Rosewarne

Nix Rosewarne has worked for most of her professional life as an actor, director, theatre-maker, and lecturer after graduating from Dartington College Of Arts with BA (hons) Theatre in 1989.

She was a core member of Kneehigh Theatre for almost twenty years as actor, director, movement director, project lead and community artist before becoming a founder artist of Wildworks, working extensively with the company between 2005 and 2011, co-creating a new language of acting specific to the Landscape Theatre form and conceiving, devising and producing new performance work in response to site in Cyprus, Malta, France and the UK. She brought to the company her extraordinary skills in physical performance, voice skills and performance direction, and her extensive knowledge of Classical mythology, which has so often been at the core of our story telling. Nix left us in 2011 to pursue her passion as an educator.

An indelible memory: While playing the role of Persephone, she abseiled down a tin mine, in the dark, wearing a ball gown and singing a Japanese Enka song.

Mydd Pharo

After completing his studies in Theatre Design at Wimbledon School of Art and Fine Art at Falmouth University, Mydd became a Founding Artist of Wildworks. The youngest member of the team, he soon demonstrated a huge talent for creating extraordinary environments and imbuing sites with story. He’s a master of the epic and the intimate, and played a significant role in shaping the company’s artistic vision — pushing boundaries and challenging conventions.

Over the course of two decades, Mydd worked on every Wildworks project. He became the company’s Artistic Director in 2020, steering it through the difficult years of the pandemic. During this time, he created Meet Me at the Edge and Earthlings Assemble, later emerging to conceive and direct Uncommon Land, I Am Kevin, and We Are Shining, culminating in Stranger Beasts.

Mydd brought to the company his remarkable skills as a visual dramaturg, his wit, his magic, his care, and a Fine Art sensibility. He left his role as Artistic Director in 2024 to carve a new path & develop the work with his own company, DAUR.

Alongside his two decades with Wildworks, Mydd has also collaborated with companies including Punchdrunk, the National Theatre, Shakespeare’s Globe and more…

You can find out more about Mydd at www.myriddinpharo.com.

Photography credits:

Steve Tanner & Ian Kingsnorth